The skin was stretched tight, paler than the rest of her body. Like warm honey. Das thought if he licked it, it would taste different from the rest of her. Instead he gently placed one hand over his wife’s belly and continued staring at it.

She sighed from somewhere above his head. “Your hands are cold,” she grumbled.

He took his hands away and repositioned the nightie over her stomach before he kissed it for the third time that morning. Anita sighed again.

“What’s wrong?”

“Everything. The usual. It doesn’t matter. He’ll come soon.”

“She,” Das corrected.

Normally they would get into a loving tug-of-war over names and gender. But Anita had been growing tired in the last few weeks of pregnancy. She was weary of all the people patting her belly, asking her when the child was due, offering suggestions on pre-natal and post-natal care, giving her oranges she’d craved for through the pregnancy. She wanted to have the baby and be done with it.

Das was a lot more enamoured by the invisible but very powerful being that was kicking his wife’s gut. He almost did not mind that he’d not made love to her in the last few months. They had been married twelve years and had been trying for a baby for eight of those years.

“Biju, I’ve been having bad dreams,” Anita said. She looked up at Das from her hands. He was sitting at the edge of the bed, beside her feet. He placed his hands on her swollen ankles.

“I know. I sleep next to you, remember? And we don’t do much to tire me out anymore, so I don’t sleep as deeply as...” he trailed off, smirk fading, seeing Anita was not going to crack a grin.

“We’ve waited so long, I just think something is....” she trailed off. She looked down at her hands again, which were splayed over her belly.

Das did not say anything. He continued to rub her feet, pressing down and easing kinks in the parts he knew ached most.

**

“Still no news from your parents?” It was more a statement than a question from Das. Anita’s silence bounced off the walls.

“Don’t worry about them,” he continued, “We’ll send them a picture of the baby. It’ll have some grandmother’s nose and one uncle’s unibrow, and they will love it and call us right away.”

“I’m not worrying about them, you are,” she replied.

They’d moved into his parents’ house in Kolkata for the last few weeks of her pregnancy. Das’ parents loved their daughter-in-law and usually she loved them too, but her strain was palpable. As her stomach stretched tighter and the baby kicked harder, the lines on Anita’s face deepened each day.

She missed her mother. Das knew that during their dozen years together, whenever she was particularly tired or unwell and she wept, it was because she wanted her mother. Though the pregnancy had been normal, and a blessing after so long, Anita’s want for her mother didn’t go away. Even when they were desperately trying for a child, there were times when Anita would blame her parents once she realised she was not pregnant. “They cursed our marriage,” she would say.

Das never knew what to say because he knew that she loved her parents nonetheless. His murmured dissent was all he’d offered at those times before distracting her with other things.

Anita was standing in front of the window later that day, watching motorcycles on the road whizz by, the neighbour arguing with the vegetable-seller over the price of aubergines. The older women had both tucked their long, oiled hair into buns held up by black hair-pins, one stood in the blazing May sun, the other in the shadow of her verandah. Anita heard the raised voices squabbling in melodious Bengali. She still couldn’t understand much of the language besides a few vegetable names, the words for love and anger. She promised herself her son would be fluent in both parents’ languages and in English too. He wouldn’t speak the broken English his parents spoke when they’d first met each other.

Anita remembered when she first taught Das how to speak Malayalam. She’d hoped he would impress her Kerala-village-born parents with his grasp of the language and that they would forgive him for sweeping their daughter off her feet. But her parents never understood her falling in love with a circus technician, a man outside their caste, creed and state. She tried not to remember the raised voices, threats and tears, which ended in her mother giving her the most valuable pair of earrings in her cupboard and her largest box to pack, not saying a word or shedding another tear.

Anita sighed. The vegetable-lady had moved on and could be heard complaining to her Mrs Das. Anita’s mother-in-law was a plump, maternal lady with a fierce temper and a great, big heart. Enough to nearly make Anita forget about her own mother. Mrs Das was paying no attention to the vegetable-seller’s mutterings, asking for fresh spinach (“Anita needs some greens you know. And where are those mangoes you gave me last week? No, not the Amrapalli ones, she didn’t like those much”), and checking the consistency of the tomatoes. Das had trotted downstairs to his mother. She could picture them – him grinning at the woman and answering questions about the wife and baby, while his mother sorted through the basket, asking Das whether he would eat his peas that night. It would lead to a gentle exchange, with Mrs Das deciding to ask Anita how she made his vegetables and got him to eat them, with grated coconut and cumin seeds.

Anita felt the baby kicking again. She suddenly heard a faint popping noise before she felt a warm gush between her legs.

**

Anita’s face was blotchy. She’d been crying for hours and refused to eat anything.

Das and his parents tried to calm her down, Mr Das even suggested a mild sedative, but Mrs Das wouldn’t have it. “The girl has tried for a baby for nearly ten years, she finally has one and he... his... he’s not made properly? Of course she will be upset! Don’t you dare put her to sleep, she needs to let it out!” she shouted in Bengali before storming back into her daughter-in-law’s room.

Anita was savagely blowing her nose into a handkerchief the size of a small towel. “When can I see him?” Her hair was tightly bound in a bun, she was wearing her own navy-blue nightgown – one she’d made especially for her breastfeeding days, with a zip that opened the front of the gown down to the top of her belly.

Mrs Das took the liberty to sit on the bed next to Anita, and shook her head. “He’s too weak, daughter.” This led to more tears as Mrs Das expected. She opened her arms and drew Anita into them patting her on the head with one hand, rubbing her back with the other. Through sobs, Anita spluttered, “It’s all her fault... That horrible mother of mine, her drishti ... She won’t... She just won’t accept Biju and me...”

Outside the room, her husband and father-in-law were speaking to a pair of doctors treating the baby.

“I don’t understand... If it is so bad, how did the doctors not see this before? Anita had scans taken through her pregnancy...” Das trailed off.

“This isn’t something scans can pick up yet,” the male doctor responded.

“Wait, so basically his kidneys are compromised and, and his waste is poisoning him and you can’t do anything about it?” Mr Das asked. The female doctor nodded, and noticing how anxious the Das men looked, said, “He’s on dialysis, he’ll regularly need that. He’s also on IV fluids... All we’re saying is that right now he’s too weak for surgery. We can only do that when he’s stronger. Aside from that everything is fine.”

“Aside from his nine fingers and his kidneys pumping poison into him? Forget the fingers, but, his kidneys? FINE?” Das shouted.

The doctors shifted uneasily. Senior Das placed his hand on his son’s shoulder and asked them, “How long do you think that would be?”

The two in white coats exchanged looks. The woman answered, “It could be anything between six months to a year or two. We can’t tell. It depends entirely on the state of his health. Nothing can be done till he is much better.”

***

It was the day after his surgery, and Varun hadn’t woken from anaesthesia. His heart had stopped once during surgery and once after. He’d been revived, but the Das’ remained worried. His doctors argued their case. “The procedure went fine, everything is alright now. He is in good health, his kidneys are functioning normally...”

“Then why isn’t he waking up?” Anita asked them early that morning.

“It could be his heart. After the kidneys poison his system, it could have slowly reached his heart, and it could be-” “Could?” Anita spat.

When they were alone, Mrs Das had gently asked her, “Child, have you had any news...” she hesitated before finishing, “from your parents?” She’d heard her daughter-in-law speak of her parents often, but they were mentioned less and less over the years. She’d never asked about them before.

Anita’s head swirled with thoughts of her three-year-old never waking up again; she did not even notice Mrs Das broaching a taboo topic. “No, Ma. I would’ve told you if they had...” She took a deep breath and put her hand on her mother-in-law’s. “Don’t worry, he’s not going to leave us, he has plenty of time to see his other grandparents.”

Later when Mrs Das was asleep, Anita and the deep bags under her eyes slipped away from the hospital and the smell of antiseptic to send her parents another letter. After slipping the letter into the post-box, she spent a few minutes in the bustling car park, watching other families come and go. Sometimes she wished for a nicotine habit like Das’ that could give her a few moments of peace every day. When she returned to the waiting room, she looked at her family for a moment before entering.

Her husband hadn’t shaved and smelled of sweat and cigarettes. Mr Das had gone home with her the night before, so they were both bathed and fresh that morning. Anita wanted to wash as well, but chose not to leave her three-year-old son’s bedside for very long.

She finally stepped into the room. “Any news?”

“In the five minutes you’ve been away? No.”

Mrs Das hissed at her son’s sarcasm. Anita barely noticed his bite anymore. Both their lives centred around Varun, his frequent trips to the hospital, his dialysis, infections, medications and fevers.

While Das had been with the circus, Anita had also started home-schooling Varun – she began with English and moved to Math while Mrs Das taught him (and Anita) Bengali alphabets.

As soon as Varun was in better health, he was sent off for surgery. Anita was almost disappointed. She’d gotten used to her baby running about their house in Kolkata when he had the strength, speaking in a muddle of languages to his toys, helping in the kitchen. He was a cheerful child despite spending much of his time in the hospital – he didn’t realise that he wasn’t ordinary. It never occurred to him to ask his mother why he rarely met other children at the hospital or why he had nine fingers instead of ten.

**

Some weeks after Varun’s surgery, a letter arrived in the Das’ post-box. It had Anita’s handwriting on it. A letter to her parents that came back from Kerala with a ‘Return to Sender’ stamp.

Amma and Appa,

Varun is not well. I don’t want to take up any of your time so I will just briefly tell you.

He went into surgery for his kidney trouble. It went okay and his kidneys are much better now. But for some reason he is not waking up from his anaesthetic.

That’s all I wanted to say. I’m not sending a picture of him this time.

Your only daughter,

Anita Mammen-Das

Mrs Das saw that the letter had been unsealed and re-sealed, so she did not tell her daughter-in-law about its return. Why upset her even more? She threw it away and returned to her grandson.

Varun had been moved home after many weeks in the hospital, machines pumping breath into his body for the first few weeks. His kidneys functioned and soon his lungs did too, but he showed no signs of waking up, confounding all medical staff who examined him.

Das was distraught, while his wife robotically went about tending to Varun, washing him and changing his clothes everyday, checking that his IV fluids were flowing well. The grandparents were doubly unhappy, over Varun and also their son and daughter-in-law’s downward spiral. One of the two always spent the night on a mat in Varun’s room, while the other cried themself to sleep in the bed meant for them. Das’ regular snipes about his wife’s non-existent family did nothing to solve the matter. Even his mother’s stern reproaches didn’t stop him.

The old lady finally told him one morning over their chai: “Go back to work. There is nothing you can do here.”

Das dipped his biscuit in tea, not replying. He took it out too late – it disintegrated and fell into the milky tea, splashing his white vest. He sighed, finally looking up into his mother’s eyes, which were gleaming.

“That’s what happens when you try to ignore your mother and shout at your poor wife.”

Das looked down again. For the first time there was shame in his eyes. Mrs Das didn’t need to look at his eyes. She reached out and placed her hand over the tanned knuckles tightly gripping the tumbler of tea. “We’ll look after them till he wakes up. And he will. Don’t you worry, puchka.”

Das waited a moment before getting up, his chair grating. His jaw was clenched tight as he headed towards his bedroom, their bedroom, he reminded himself. When he got there, he pushed the door to open it, but it was locked.

Then he remembered that Anita had started locking the door while she dressed.

When Anita stepped out of her room she nearly tripped over her husband. “What are you doing?” she asked. Das stood up and walked into the room, gesturing for her to follow. Anita frowned, opening her mouth to say, “Varun-”

“Is asleep. And your blouse isn’t buttoned properly.”

Frowning, she stepped back into the room, reaching behind, towards her blouse. She hadn’t had the time to wash her regular blouses, and she hated using the ones with buttons she couldn’t reach.

Das didn’t say anything, simply shutting the door and reaching to help her. Anita dropped her hands in shock – it’d been months since Das touched her. She frowned deeper and started to squawk when she realised he was undoing her buttons.

When Anita turned, Das placed his hands on her shoulders. “I’m sorry,” he shocked her once more. He continued, “If I hadn’t married you... if you’d married another... you wouldn’t, this wouldn’t...” He trailed off.

Anita slowly took his hands off her shoulders and stared, expressionless, into his eyes for a moment. Then she reached for the safety-pin that pinned her sari to her blouse and removed it, placing it in her husband’s palm.

Das finally allowed his eyes to tear up.

**

Amma and Appa,

Here is the last picture I am sending you of my son, Varun Das. He is still asleep, but he has grown quite big in the last one year since his surgery.

I’m sorry I’ve wasted yours and my time writing to you the last twelve years. I thought one day you would forgive me. Since that isn’t going to happen, I will never contact you again.

I wish you all the happiness in the world.

Anita Das

**

Das jumped out of the black taxi, yelling to the driver, “Just throw my bags inside the gate, please, thank you brother!” and ran towards his parents’ front door.

The door was open, his mother was standing at the entrance talking to the neighbourhood milk-man about the jump in milk prices.

“Son! Did you get my message about-”

Das was not interested in anything besides getting to his son. “Ma, hi, I’ll come to you...” Mrs Das yelled back the blur that was her son, “Wait, there’s someone in there, come back and I’ll tell you what... Bijoy!”

Das had run up the stairs to Varun’s room by then. The door was ajar, he pushed it open and saw his son, grown since the last time he’d seen him. There were two things that caught Das’ eye – Varun was sitting upright, not quite wide-eyed, but dozing off because his legs were being massaged by a grey-haired woman.

Das realised the smell that had invaded his senses was that of coconut oil – something he’d only smelt in his wife’s hair and cooking before. When the woman looked up at him, hesitantly, he realised why she was lovingly kneading the child’s oily legs.

The eyes he was looking into were identical to his wife’s dark brown eyes.

He stood speechless while Varun squealed for his father and tried to stand up. Das went over to his little boy and wrapped his arms around him. He stood there for several moments before Varun stumbled and the woman told him, in Malayalam, “Sit down, your legs aren’t strong enough yet.” Das was torn between shouting at her for telling his son to stop hugging his own father, or to be grateful she finally came.

Anita broke the silence. She’d slipped in without her husband realising.

“Ma, it’s fine.” There was a long, awkward silence before she continued in Malayalam, “You remember Bijoy.”

Her mother nodded, standing up and wiping her oily hands on her sari. She mumbled about leaving them alone before Das’ manners kicked in. He quickly stepped over to where his mother-in-law stood and bent to touch her feet respectfully. In broken Malayalam he said, “It’s good to meet you again, Mother.”

The woman froze, not knowing how to react. She looked at her daughter with big eyes and fled out of the room stifling a shameful sob.

Anita’s expression changed to one of amusement. “Thank you for rubbing that in.” She embraced her husband, who still had stars in his eyes.

Their son giggled and bounced in his bed. His lengthened frame made the wooden frame creak loudly. Das went and sat by him, pulling his wife and drawing her into their circle as well.

“Want to tell me how that happened?” he asked.

Anita shrugged. “I don’t really know. She just showed up out of the blue some weeks ago. And-”

“Your father?”

Her eyes fell, “He passed away last month... They’ve been with my elder brother’s family. His wife wasn’t good to them and Acha had been unwell. He wanted to see me, but...”

“But he’s a stubborn old coot.” Das corrected himself, “Was. Sorry.”

“Biju!” She gasped.

“It’s true, you know it.”

“Well, the stubborn old coot left us his old house.”

“Coot, coot, coot, coot” Varun echoed.

His father laughed and hugged him again before the boy said, “Amamma kissed me awake. Didn’t she, Ma?” He tripped over the new word he had learnt for his grandmother.

Das cocked an eyebrow, switching to Hindi, which Varun did not understand yet. “Load of crock. What happened, what woke him?”

“Actually...” Silence.

“You’re joking.” Das’ voice was still disbelieving.

“Well, she just kissed him on his cheeks. Both. And she cried. On him. And that night he woke up. We called the doctor, the same one you know, and he came home at 2 in the morning to check him. He said he is fine. That everything is alright. No explanations.”

Varun was whining, pulling his father’s shirt while Anita spoke. When Das looked at him incredulously, the boy said, “I have to go bathroom.”

The parents exchanged looks. “Number two,” the boy added.

His father broke into a huge grin.

**(the end)**

moonshine borealis

Friday, 13 February 2015

Monday, 12 January 2015

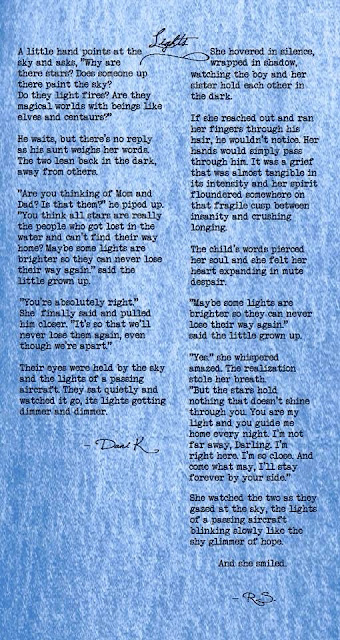

lights

a collaboration with a poet friend. for the passengers of the still missing MH370, victims of MH17 and QZ8501, and all their families.

Wednesday, 31 December 2014

where do we go now?

I’ve realised that I end up taking stock only at the end of the year when it hits me that I need to change the dates on letters and posts yet again. Just when one gets used to writing 2014, it changes to 15. And so on.

2014 was maddening for me. In good ways and in some very, very bad ways. The beginning of the year was not too great and it went on to become horrific for my family and I when we lost my cousin and his wife on Malaysia Airlines jet MH370. I worked on auto-pilot that month till I was packed off by my mother to Beijing to help with my cousin’s two little boys.

Last night a missing aircraft was found in the Java Sea, which brought back memories of MH370 all over again. I’ve had to accept now that we will never know what happened to my two family members on the flight, along with 237 others. It wasn’t so much the incident itself that pushed me over the edge. It was humanity itself. People, their reactions, their inability to leave it alone instead of pondering the million things which could have happened, it all got to me. And while many people (including ones who barely knew me) were surprisingly thoughtful, many were also surprisingly callous.

The world seems to have moved on, but I don’t think my family ever will. Each time we look at my nephews or hear about their nightmares, their fears or them missing their parents, we will be reminded about what happened, or in this case what could have happened.

While the first half of the year seems to have been dominated by this, the second half brought more changes. The shift to a new city, a new part of the country, was something inevitable that I’d been putting off for a couple of years. The capital always seemed a daunting place, especially to someone from a relatively placid south Indian city.

Delhi has so far been everything that people warned me about, but other things as well. Yes, it’s aggressive and loud, it’s callous, ruthless, does everything it can to make you stronger. But it also has options like no other city. It’s hard to be lazy in Delhi. I’d planned a long break, but somehow, even without really pushing myself to find work, I’d got three job offers within three weeks of moving. And all in a new field (after I’d decided the media didn’t do it for me anymore).

The city always has something going on, and for everyone. For someone who doesn’t like noise and big crowds, even Chennai didn’t have too many options sometimes. But the capital is full of old buildings, beautiful monuments, large green parks, and I’ve found book stores to roam in when I’m bored. Dance performances, rock shows, talks and lectures, you name it and Delhi has it. If I feel like going out, I know I can. And yes, you have the large groups of teenagers and couples everywhere, but it’s not unusual to see some lone rangers doing things on their own. For every action here, there *is* an equal and opposite reaction.

It may not be home yet, it may not have a beach or endless options for a cup of good filter coffee, but I’ve noticed a few things not relating to just the aggressive gun-toting Haryanvis and Punjabis here. While Chennai was placid and laid-back, I’ve realised people there are too inert sometimes. If a boy had arbitrarily reached out for a girl from behind and grabbed her at a party in Delhi, it would not go easily dismissed. Whereas I’ve seen the very same thing happen in Chennai in front of a large group (everyone pretended it didn’t happen, including her male best friend and even me). Peoples’ sense of their own rights is very acute here in Delhi. Women’s safety is a big issue, and hence made a hue and cry about. I find changes in my own behaviour in less than two months here. Even jokes made about women are not as easy to forget as before. In a country full of culture, rich in history, people seem to have forgotten about equality and respect. Not just for the opposite gender, but for humans in general. In that sense Delhi is a lot more accepting of different types of people than Chennai.

If I am likely to stand up for myself or another woman in my hometown, no doubt I will now be classified as a pushy Delhi-ite. But in the capital, I would just be normal. And while I was part of a small group in the ‘unmarried girl in late 20s’ section in my hometown, here I’m just a girl, or a woman, depending on who’s looking. The tendency to colour outside of the lines is much more common in this city, which is something I can definitely get used to.

The year has also taught me a little more about myself. Like all other years, I suppose. It has brought me some surprising friendships and bonds, and has allowed me to let go of some surprisingly unhappy friendships too.

I can’t say I have any regrets. Maybe I could have been more patient with a few people, but I’ve become more attentive to time – whom I give it to, and why.

For the first time perhaps, I have no idea where the next year will take me. Physically, I will be in the same city. But emotionally and mentally, I’m completely unprepared for what’s coming. I’ve seen many people come and go, but only this year did I realise just how everything can change in an instant. With a single phone call or text, lives and paths can be altered forever.

I know I’m tough enough to handle whatever is coming. I just hope I’m accepting enough to manage the joys as well, without asking too many questions or wondering how it could turn to ashes in the future.

2014 was maddening for me. In good ways and in some very, very bad ways. The beginning of the year was not too great and it went on to become horrific for my family and I when we lost my cousin and his wife on Malaysia Airlines jet MH370. I worked on auto-pilot that month till I was packed off by my mother to Beijing to help with my cousin’s two little boys.

Last night a missing aircraft was found in the Java Sea, which brought back memories of MH370 all over again. I’ve had to accept now that we will never know what happened to my two family members on the flight, along with 237 others. It wasn’t so much the incident itself that pushed me over the edge. It was humanity itself. People, their reactions, their inability to leave it alone instead of pondering the million things which could have happened, it all got to me. And while many people (including ones who barely knew me) were surprisingly thoughtful, many were also surprisingly callous.

The world seems to have moved on, but I don’t think my family ever will. Each time we look at my nephews or hear about their nightmares, their fears or them missing their parents, we will be reminded about what happened, or in this case what could have happened.

While the first half of the year seems to have been dominated by this, the second half brought more changes. The shift to a new city, a new part of the country, was something inevitable that I’d been putting off for a couple of years. The capital always seemed a daunting place, especially to someone from a relatively placid south Indian city.

Delhi has so far been everything that people warned me about, but other things as well. Yes, it’s aggressive and loud, it’s callous, ruthless, does everything it can to make you stronger. But it also has options like no other city. It’s hard to be lazy in Delhi. I’d planned a long break, but somehow, even without really pushing myself to find work, I’d got three job offers within three weeks of moving. And all in a new field (after I’d decided the media didn’t do it for me anymore).

The city always has something going on, and for everyone. For someone who doesn’t like noise and big crowds, even Chennai didn’t have too many options sometimes. But the capital is full of old buildings, beautiful monuments, large green parks, and I’ve found book stores to roam in when I’m bored. Dance performances, rock shows, talks and lectures, you name it and Delhi has it. If I feel like going out, I know I can. And yes, you have the large groups of teenagers and couples everywhere, but it’s not unusual to see some lone rangers doing things on their own. For every action here, there *is* an equal and opposite reaction.

It may not be home yet, it may not have a beach or endless options for a cup of good filter coffee, but I’ve noticed a few things not relating to just the aggressive gun-toting Haryanvis and Punjabis here. While Chennai was placid and laid-back, I’ve realised people there are too inert sometimes. If a boy had arbitrarily reached out for a girl from behind and grabbed her at a party in Delhi, it would not go easily dismissed. Whereas I’ve seen the very same thing happen in Chennai in front of a large group (everyone pretended it didn’t happen, including her male best friend and even me). Peoples’ sense of their own rights is very acute here in Delhi. Women’s safety is a big issue, and hence made a hue and cry about. I find changes in my own behaviour in less than two months here. Even jokes made about women are not as easy to forget as before. In a country full of culture, rich in history, people seem to have forgotten about equality and respect. Not just for the opposite gender, but for humans in general. In that sense Delhi is a lot more accepting of different types of people than Chennai.

If I am likely to stand up for myself or another woman in my hometown, no doubt I will now be classified as a pushy Delhi-ite. But in the capital, I would just be normal. And while I was part of a small group in the ‘unmarried girl in late 20s’ section in my hometown, here I’m just a girl, or a woman, depending on who’s looking. The tendency to colour outside of the lines is much more common in this city, which is something I can definitely get used to.

The year has also taught me a little more about myself. Like all other years, I suppose. It has brought me some surprising friendships and bonds, and has allowed me to let go of some surprisingly unhappy friendships too.

I can’t say I have any regrets. Maybe I could have been more patient with a few people, but I’ve become more attentive to time – whom I give it to, and why.

For the first time perhaps, I have no idea where the next year will take me. Physically, I will be in the same city. But emotionally and mentally, I’m completely unprepared for what’s coming. I’ve seen many people come and go, but only this year did I realise just how everything can change in an instant. With a single phone call or text, lives and paths can be altered forever.

I know I’m tough enough to handle whatever is coming. I just hope I’m accepting enough to manage the joys as well, without asking too many questions or wondering how it could turn to ashes in the future.

Tuesday, 30 December 2014

457 Oak Wood Circle

I stood outside the house. 457 Oak Wood Circle. How pretentious did that sound for an Indian home? Did I really want to meet the people inside? What if they were having a get-together? What if they told me to go away? Worse, what if they were having a party and invited me in? What would my family say if they knew where I was?

The air was crisp as I took a deep breath. Fresh and a welcome change from my hometown’s heat and pollution. The house was large from the outside, it looked tastefully done with its manicured garden and ornate black lamps hanging from various ceilings. I didn’t hear any voices – what if they weren’t home.

Answering my question, a figure walked through one of the rooms while switching on the lights. I couldn’t tell if it was a man or a woman. Then I heard a dog bark. My heart jumped. Anyone who owns a dog and is good to it has to have a good heart, even if it’s buried somewhere deep. My friend had laughed when I told her that. But I’d always believed it to be true.

So I opened the gate and shut it behind me, as quietly as I could. I walked up the sloping driveway. Another tiny rose garden on my right and two cars before me – a silver small one and a larger red one. Who was the second car for?

I should not judge a book by its cover, I reminded myself. It had happened very often as a child with my mother. She never married. We were constantly judged. You get the gist.

I tried not to think of my mother. Memories from my childhood, adulthood, from her funeral – it was all too much.

I took a deep breath and looked at some of the other houses. The smell was unlike anything I had ever come across. Fresh, clear, leafy, it cleared my head as I breathed it in. If it had a colour, it would be one of those deep orangey-browns, I decided.

The other houses were as perfect as the one I stood in front of. Spacious lawns, big windows, clean cars in the driveway.

I turned around and looked at the door once more before walking up to it. I wiped my palms on my jacket. My heart was beating so hard that I didn’t hear the doorbell when I rang it.

The door was opened by a older woman, dressed neatly in a sari with her hair tied back in a braid. She smiled politely.

“Hi. Can I help you?”

“Does Rahul Wadia live here?”

“Yes. Both of them do.”

“Both?”

“Yes, junior and senior,” she laughed.

I swallowed. “Well, I think I’m here for the senior.”

“You think?”

“I’ve never met him before, so...”

Her eyes grew suspicious. “Who are you?”

“I’m his son.”

I wondered if she was going to let me inside.

The air was crisp as I took a deep breath. Fresh and a welcome change from my hometown’s heat and pollution. The house was large from the outside, it looked tastefully done with its manicured garden and ornate black lamps hanging from various ceilings. I didn’t hear any voices – what if they weren’t home.

Answering my question, a figure walked through one of the rooms while switching on the lights. I couldn’t tell if it was a man or a woman. Then I heard a dog bark. My heart jumped. Anyone who owns a dog and is good to it has to have a good heart, even if it’s buried somewhere deep. My friend had laughed when I told her that. But I’d always believed it to be true.

So I opened the gate and shut it behind me, as quietly as I could. I walked up the sloping driveway. Another tiny rose garden on my right and two cars before me – a silver small one and a larger red one. Who was the second car for?

I should not judge a book by its cover, I reminded myself. It had happened very often as a child with my mother. She never married. We were constantly judged. You get the gist.

I tried not to think of my mother. Memories from my childhood, adulthood, from her funeral – it was all too much.

I took a deep breath and looked at some of the other houses. The smell was unlike anything I had ever come across. Fresh, clear, leafy, it cleared my head as I breathed it in. If it had a colour, it would be one of those deep orangey-browns, I decided.

The other houses were as perfect as the one I stood in front of. Spacious lawns, big windows, clean cars in the driveway.

I turned around and looked at the door once more before walking up to it. I wiped my palms on my jacket. My heart was beating so hard that I didn’t hear the doorbell when I rang it.

The door was opened by a older woman, dressed neatly in a sari with her hair tied back in a braid. She smiled politely.

“Hi. Can I help you?”

“Does Rahul Wadia live here?”

“Yes. Both of them do.”

“Both?”

“Yes, junior and senior,” she laughed.

I swallowed. “Well, I think I’m here for the senior.”

“You think?”

“I’ve never met him before, so...”

Her eyes grew suspicious. “Who are you?”

“I’m his son.”

I wondered if she was going to let me inside.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)